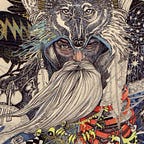

The Sixteen Wakan Tankas. An Introduction to Lakota Metaphysics.

Mitákuyepi. My name is Daniel Garber. An elderly Lakota sun dancer once gave me the Lakota name Woičákȟa Wakhúwa, which in English means “Seeker of Truth.” My family is from the high plains of Montana in the USA. I grew up on a family farm that was homesteaded on land that lies on the border between pre-treaty Blackfoot and Nakota lands. Lakota and Crow peoples probably left their energies there as well. I am an ikče wičaša, but I am a wašicų and I suffer from ancestral guilt.

The preceding is something like the customary Lakota way of introducing oneself to strangers. But this is not about me. This is about David C. Posthumus, PhD. He is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of South Dakota and he published a book in 2018 entitled “All My Relatives: Exploring Lakota Ontology, Belief and Ritual.” This is about that book, and the 2015 dissertation that preceded it, entitled “Transmitting Sacred Knowledge: Aspects of Historical and Contemporary Oglala Lakota Belief and Ritual.”

When he graduated from Michigan State University in 2007, Posthumus wrote his senior thesis paper entitled, “The Pipe Religion, Spirit World, and Lakota Spirituality.” He began doing field work with the Lakotas at that time, and it seems he has been at it ever since.

The literature on old Lakota philosophy is based on interviews done with Lakotas since the nineteenth century. Much of that early work was recorded not by anthropologists, but by trappers and traders and agents of the US government, who happened to find themselves living next to old Lakotas. This means that much of that information did not come directly from the source, but rather through the interpretation of outsiders, who were sometimes not sympathetic, and who certainly were not products of the culture upon which they were reporting. This means the work was not professionally disciplined. Much was probably lost in translation.

Much was also lost due to colonial practices of repression and oppression, which sought to tame and civilize what they saw at the time as savage peoples. This was accomplished through enforced re-education of Lakota children in boarding schools and the criminalization of traditional ways. For example, it was illegal to practice traditional Lakota religious ceremonies in the open until The American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978. (Some contemporary Lakota practitioners do not like to refer to what they do as religion, due to the negative associations, but rather refer to it as spirituality.) As a result, many modern Lakotas do not know or practice their own ways. They have been acculturated into the dominant culture, but not always well.

The Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota is the home of the mighty Oglala Lakotas. Per Capita Income on Pine Ridge is $7,773. The unemployment rate on the rez is 80%. A recent study found the life expectancy for men to be 48 years; and for women to be 52 years. The Pine Ridge Reservation has the highest infant mortality rate in the United States. Only a small minority population of the Lakotas still speak the language. Even this is not the “old” Lakota. It is a newer version of the language. It seems the dominant culture did its job well — if their goal was to destroy the old Lakota ways. But they didn’t wipe them out completely. Some practices survived by going underground, including the iconic Lakota Sun Dance. But how can we reliably determine what those practices and beliefs were when those who did and had them are now all dead and gone?

The best surviving window we have into the old ideas of Lakota philosophy is through the writings of Dr. James R. Walker. Walker spent eighteen years, from 1896 until 1914, living in South Dakota as a physician on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Three volumes of documents have been published (Walker 1980, 1982, 1983) that have become primary sources for the study of Lakota spirituality. Walker’s notes were filled with conflicting and confusing accounts from his sources. The published material is the end result of weeding out much of Walker’s conflicting notes. So again, much has been lost. There is even speculation among some contemporary Lakota scholars and writers that Walker’s informants were purposely misinforming him, partly because the material was banned and illegal, and partly because they didn’t trust such knowledge to a representative of the dominant culture, even though he claimed to be an initiated Lakota shaman.

David Posthumus wades into this quagmire and tries to do his best to find the truth — to search out the true old Lakota ways, philosophy and spiritual practices. He does this by reviewing and surveying the old conflicting sources, with a concentration on the Walker material. He supplements this with his own informants. He also attempts to do this in line with modern anthropological practices, designed to eliminate cultural biases that at one time led to colonial prejudicial judgments about the so-called savages.

As a professional anthropologist, Posthumus is writing for an audience of fellow academics, in particular for anthropologists. As a result the book is full of academic jargon. This is not a book for the casual reader interested in shamanism — unless you are highly motivated to wade in to pan for the valuable nuggets of Lakota knowledge, of which there are many to be found. I myself was a Philosophy major, so I was trained to recognize and understand academic jargon, but I find the anthropological jargon found here particularly dense and hard to endure. For example, we are told this book is about “Ontological Ethnometaphysics.”

In Posthumus’ own words:

“This project explores traditional Lakota ontological conceptions as they operated within the magico-ritual realm, largely in the nineteenth century. I do not claim that these underlying beliefs apply equally to all Lakota people at all times or that multiple ontologies do not operate situationally and simultaneously in Lakota culture and thought. Adopting an eclectic new animist or post-humanist position and one grounded in ethnohistorical methods, I explore Lakota animist beliefs regarding the personhood of rocks, ghosts or spirits of deceased humans, animals, meteorological phenomena, familiar spirits or spirit helpers, medicine bundles, and so on. In this study I draw on insights from ontologically inflected anthropologies, particularly that of Phillippe Descola (2013a), in a (re)interpretation of nineteenth- century Lakota ethnography.”

In a less formal way, Posthumus says:

“One of the really cool things for me about this book is that it brings together so much of the literature on the Lakotas and particularly puts all these new things — these new theoretical ideas — new animism and stuff — into dialogue with those sources and particularly with the Delorias — with Vine Deloria’s work and with Ella Deloria’s work.”

So Posthumus is writing from a position of authority, in regard to contemporary anthropological issues, such as the question of whether Lakota practitioners are animists or shamans. In his dissertation he writes:

“Shamanism is a hotly debated and contested concept in anthropology today (see Atkinson 1992; Geertz 1973:122; and Taussig 1986). Neither shaman nor priest is completely adequate in the Lakota case. Practitioners seem to inhabit an intermediate, overlapping space between classical anthropological definitions of priest and shaman. While contemporary Lakota religious leaders are increasingly full-time practitioners, they also clearly utilize helper spirits, mediate between worlds, and are believed to leave their bodies and enter into trance states. Labeling Lakota ritual practitioners as shamans has met with some resistance and criticism, but I believe there is substantial evidence supporting the notion that Lakota ritual practitioners may be better understood as shamans as opposed to priests.”

Posthumus uses the term “shaman” unabashedly throughout. He doesn’t take on the social justice issue of whether the term “shaman” is appropriate to use at all, outside of its use in reference to the Siberian Tungus or Evenk. He does adopt the notion of “New-Animism.” New-Animism redefines what it means to be a “person.” This has something to do with what he calls “The Ontological Turn” and he credits that to A. Irving Hallowell. He uses the term “Situated Animism” after Philippe Descola, and often refers to it as Descolian Animism. Situated Animism is practical modern animism. In Situated Animism human beings are at the bottom of the natural pecking order; not at the top. When humans are at the bottom of the natural order, then it is crucial to have “allies” who are non-human persons in order to survive and to prosper.

“In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top — the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation — and the plants at the bottom. But in Native American ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as “the younger brothers of Creation.”

— Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass”

This “new-animism” redefines a person to include rocks, animals, supernatural entities, ancestors, medicine bundles, and more. Does this mean everything is a person? Although everything might not be a person, everything has the *potential* to be a person.

“I once asked an old man: Are all the stones we see about us here alive? He reflected a long while, and then replied, ‘No! But some are.’”

— Hallowell

Non-human persons live like human persons do. They live in groups like humans do. Posthumus adopts the idea of the “collective” which is the social group in which non-human persons live. A collective mimics the lifestyle of humans who live in tribes (oyatepi) and camps (tʿiyošpaye) and families (tʿiwahe).

And so Posthumus is setting the stage for demonstrating how the Lakota philosophy is opposed to Western European worldviews. In addition to the existence of non-human persons, the natural world is not separate from the civilized world. There is no separation. The Lakota maxim mitakuye oyasʾį — We Are All Related — or Everything is Related — summarizes this worldview, but almost trivializes it.

“The realms of Lakota mythology (ohųųkaką), dreams and visions (ihąųblapi), and ritual or ceremony (wicʿoȟʾą, woecʿų) were peopled by a diverse cast of characters, mainly various animal species and spirit persons commonly encountered in the plains environment in which the people lived. In these domains human-nonhuman communication and exchange is still possible, as it was in the primordial subterranean world. Aside from Iktómi and a few other key personalities, the literature suggests that the nonhuman persons of Sioux cosmologies should not be conceptualized as monolithic, timeless, immortal, singular entities but rather as a class (oicʿaǧe) of persons, a tribe-species or collective, an oyáte.”

In Lakota mythology, Iktomi is a spider trickster spirit.

“[Iktómi] named everything that was to be found all over the world. . . .Whatever moved upon earth [i.e., animals] got its name from Ikto. We believe that he was the first to speak by using the words with which we express ourselves. Wherever there are here and there some animals that are peculiar, they were made so by Iktomi; and we believe too that he made all wild fruits. . . . He long ago named all the organs found within a man’s body, and to this day we follow those names. . . . And in the olden times, Ikto was good friends with all sorts of animals, being related to them; and they took their orders from him. . . . He was able to converse with animals who cannot speak.”

Posthumus has spent years learning and speaking the Lakota language, so much is to be learned about Lakota words and the language here. There is also an extensive Glossary of Lakota Terms and Phrases in the back of the book, before the copious Notes and References, and the ever-handy Index. He adopts a convention of spelling and printing the language that is a bit different from what I’ve become used to. It is also different from that used in his dissertation. In personal correspondence to me he explains that it is Ella Deloria’s orthography. Ella Deloria is a Yankton Sioux ethnographer and linguist.

The nuggets of old Lakota belief that make the book (and the dissertation) truly worth savoring have to do with metaphysical ideas that apply to both the human and the non-human soul. Walker’s old Lakota informants from the nineteenth century describe four parts of the soul. These four parts of the soul are themselves part of what is known as the “Sixteen Wakan Tankas” or the Tobtób Kį. The Tobtób Kį are the Four Times Four (a term used in reference to the sixteen manifestations of Wakʿą Tʿąka).

Walker calls this “the secret lore of the shamans” and gives credit to these old Lakota informants — Little-wound, American-horse, Bad-wound, Short-bull, No-flesh, Ringing-shield, Tyon, and Sword. All of these gentlemen were deceased at the time of his writing, which was 1917. Bad-wound, No-flesh, and Ringing-shield were the principal informants on the subject of doctrine. Tyon was the interpreter of the shamans, although his knowledge of English was admittedly poor. Sword wrote out his knowledge in old Lakota and that had to then be translated into English.

Walker’s account of this process, and his discovery of “the secret lore” sounds eminently plausible. Posthumus addresses the Tobtób Kį at length in his dissertation. As he explains to me in a personal correspondence, in the book he concentrates more on the Parts of the Soul, and not so much about the Four Times Four.

The Tobtób Kį are sixteen distinct spiritual entities that make up what we call Wakʿą Tʿąka. Wakʿą Tʿąka is literally translated as Great Mystery. Wakʿą is mysterious. It is mysterious because it is incomprehensible to the limited minds of mere humans. Wakʿą is sacred because it is so mysterious. Tʿąka is great. Wakʿą Tʿąka is not translated as “God.” It is not the Christian God. It is not equivalent to Jehovah. The Lakota prefer the word “spiritual” to “religious.” The word religious has connections to organized religions that have not been kind to the Lakota.

The sixteen spiritual entities that make up Wakʿą Tʿąka are benevolent, that is to say they are the good guys. Other spiritual entities exist who are not so benevolent. Those are the bad guys. The bad guys make up something called wakan šica, which is still subordinate to Wakʿą Tʿąka. All of these spiritual entities are non-human persons, but they are immortal. The higher ones play primary roles in the old Lakota myths. Each of these spiritual entities has its own appearance and attributes. They can shape-shift and appear as human. They can even marry and have children with humans.

The sixteen Wakan Tankas, or the Tobtób Kį are:

Wí — Sun

Táku Škąšką — Motion, Sky (Great Spirit)

Makʿa — Earth

Inyą — Stone

Hąwí — Moon

Tʿaté — Wind

Woȟpe — the Divine Feminine

Wakiyą — Thunder Beings

Tʿatʿąka — Buffalo

Hunųpa — Bear

Tʿatúye Tópa — the Four Winds/Directions

Yumní — the Whirlwind

Niya — spirit

Naǧi — ghost

Naǧila — Spirit-like

Šicų — spiritual potency

The first twelve are primordial and the subjects of myth. The last four are the Four Parts of the Soul. Each of the sixteen can be assigned to one of the willow poles used to construct a typical Lakota sweat lodge, or initʿi. And so the lodge becomes a symbolic ritual object incorporating these Lakota beliefs.

All of the parts of the soul are given at birth by Táku Škąšką, also known as Tʿųkašila, Grandfather Sky or the Great Spirit. The Niya is the breath of life, the animating element. If it happens to leave, the body will become lethargic and die. The Naǧi is the ghost and contains more of the character of the person. If it leaves, the body will lose consciousness and be comatose, although it will continue to live because the Niya is present. A shaman’s diagnosis of a sick patient may indicate that one of these has gone missing. In that case his/her job is to spirit travel to locate the missing spirit and try to convince or compel it to return to its body.

At first, understanding the nuances of the four Parts of the Soul is daunting. Sometimes the Niya is referred to as the ghost. Sometimes the Naǧi is referred to as spirit. Some of the confusion is no doubt due to the difficulty of translating these obscure subjects. To me, it makes sense to call the Naǧi the ghost. When one dies, the Niya and the Naǧi travel back to the stars along the spirit trail. Waniya is sometimes used as a word for star and Wanaǧi is the word for the earth-bound wandering ghosts who fail to return to the stars.

The sixteenth and last of the Tobtób Kį is the šicų. I find this one to be the most intriguing. The translations or descriptions about this are very confusing. This may be due to its very central and powerful nature. The šicų is given to the person, whether they be human or not, at birth by Táku Škąšką. But the šicų is literally very powerful medicine. It is the power that can be bestowed on a shaman by the high Spirits. A shaman can receive Buffalo or Bear or Thunder Being šicų, directly from the spirit, usually in dream vision or in ceremony. Medicine that is received in this way is kept in a medicine bundle, not surprisingly called a wašicų. The medicine that one might receive from the Eagle is the Eagle spirit’s šicų. Such a thing can reside in a relic or a fetish. (This is why, in my opinion, the šicų does not return to the stars with the other parts of the soul.) The šicų can be preserved in a lock of hair, such as in the Keeping of the Soul ceremony. One can capture the šicų of your enemy by taking his scalp. Animal parts can contain the šicų of the animal. Knowledge of and control of the šicų is crucial and central to the healing and curing practices of the Lakota shaman. Mitʿawašicų is the Lakota for “my spirit helper.”

“Medicine men accumulate šicųpi (plural form of šicų) mainly through multiple vision quests throughout the life cycle. In successful or correctly performed healing rituals the practitioner invests one or more of his šicųpi or part of his collective šicų in the patient or an object. This is necessary in order to renew or make over the patient (pʿiya or wapʿiya) and hence to cure (various forms of the stem asniya ‘to cause to recover, to cause to be well’), restoring wellness or balance.”

“Sicun means ‘leaving your spirit or your influence someplace.’ If you’ve ever read a book and got a sense of the author’s feelings, then that’s something like the meaning. The spirit of the author is in that book. Or it could be that somebody feels your presence when you’re not there; that’s your Sicun.”

— Albert White Hat in “Zuya: Oral Teachings from Rosebud” page 77.

The fifteenth Tobtób Kį is somewhat problematic. The description of the Naǧila is very obscure. It only appears in the Walker material. Few other sources seems to refer to it, so there is little corroborative evidence of its existence. One source suggests that the “Ton” (tʿų or tȟúŋ) is the same thing as the Naǧila. In the language of the shamans, Tʿų is “a kind of spiritual potency endowed in sacred things.” For this reason, in the book Posthumus instead concentrates on the other three parts of the soul, although he describes other parts as also important — the mind, the heart and one’s personal power.

“The constituent elements of Lakota interiority included the niyá ‘life, breath’, naǧi ‘spirit, soul, ghost’, šicų ‘familiar, “guardian spirit,” imparted nonhuman potency’, wacʿį ‘mind, will, intellect, consciousness’, cʿąte ‘heart, feelings, emotions’, and wowašʾake ‘strength, power’. Essentially, the combined niyá, naǧi, and šicų constitute a triune conception of the soul or spirit, a common archetype cross-culturally, but the wacʿí, cʿąté, and wówašʾake are no less significant in terms of the subjective self as a whole. However, I focus here on the triune niyá, naǧi, and šicų, which were conceptualized as the wakʿą aspects of human beings and hence immortal, having no birth or death.”

So Posthumus leaves the status of the fifteenth Wakʿą Tʿąka up in the air, or unresolved. In a personal correspondence with me Posthumus acknowledges that this is an open and unresolved issue. In my opinion the fifteenth Wakʿą Tʿąka could be ascribed to the wacʿį, or mind referred to above. This makes sense, since the mind is consciousness. And when one dies that consciousness leaves the body, presumably to make the voyage with the other parts of the soul back to the stars on the spirit trail (wanaǧi tʿacʿąku). Another word for mind is tʿawacʿį. As a matter of fact, a Lakota phrase describing the “mind and soul” is tʿawacʿį wicʿanaǧi kicʿi.

“Perhaps it is the legacy of animism and a relational ontology that has allowed Native American spirituality to flourish in a modern world in which many other religious traditions are threatened or endangered. Perhaps this legacy has allowed native peoples to escape the spiritual disenchantment and secularization characteristic of much of the West, which paradoxically motivates many Westerners to seek spiritual succor and fulfillment through participation in native ceremonial traditions. All speculation aside, in an era of increasing polarization, ethnic conflict, sectarian violence, and ecological crisis this study demonstrates just how much we all can learn from Sioux philosophy and spirituality in terms of abolishing the destructive and shortsighted nature/culture dichotomy and living respectfully with other life- forms in a multispecies world.”

— David C. Posthumus, “All My Relatives: Exploring Lakota Ontology, Belief and Ritual,” page 219.

Copyright © 2020 Daniel Garber

The content of this article first appeared in a highly edited form in the Spring 2020 issue of Sacred Hoop magazine. http://sacredhoop.org